For as long as professional soccer has existed in the United States, there has been drama and conflict between the alphabet soup of entities and organizations controlling the game. The casualties of these conflicts have been hundreds of clubs, and entire leagues, dating all the way back to the original American Soccer League of the 1920s and 30s. And the latest front in the seemingly never-ending American Soccer Wars (that’s #SoccerWarz for all the hip kids) is bubbling just beneath the surface: MLS vs. USL.

Prelude to War

Like many wars throughout human history – soccer or otherwise – this one has its roots in a previous conflict.

Back in 2009, the United Soccer League organization was sold off to a group called NuRock Holdings, with little-to-no input from the team owners. This didn’t sit well with many of them, and a rebellion known as the USL Team Owners Association (TOA) popped up. Spearheaded by Traffic Sports (you may remember them from the FIFA raids in 2015), owners of Miami FC (no relation to the current USL team with the same name), the 9-club group would split off and go on to form the second incarnation of the North American Soccer League, planning to begin play in 2010.

Coincidentally, 2009 was also the debut of the Seattle Sounders in MLS, the first in a wave of expansion teams that was plucked from a lower division league.

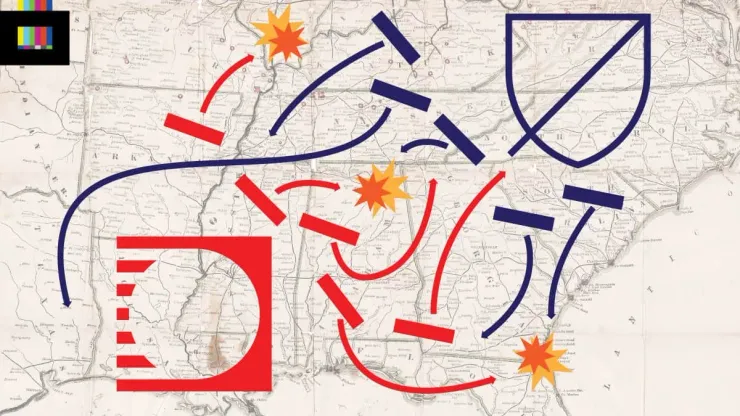

These two events were the sparks of an ongoing revival of intense competition and maneuvering between different pro soccer competitions in the US. We’ve seen lawsuits, a combined USSF-operated 2nd division league, alliances, dozens of clubs relocate, switch leagues, go on hiatus, or outright fold, and the entire NASL flash out of existence as a result of this chaos.

Since 2009, a total of nine (ten if you include Sacramento Republic FC who were awarded an MLS spot but later had the bid collapse), organizations have joined MLS from a lower division. Seattle, Portland, Orlando, Cincinnati, Nashville, and St. Louis (USL minority ownership is a part of the MLS bid but USL team branding did not survive) joined from USL, while Montréal, Minnesota and Vancouver came from the NASL (while they did not officially ever play in the league, the Whitecaps were part of the TOA breakaway group and were aligned with the NASL by the time they moved up). That’s more than a third of the league’s makeup. But the practice of elevating proven fanbases with established branding has been an unquestionable success for the league, so who can blame them?

While MLS was hand picking the ripest fruit from the lower divisions, USL was reaping tangential benefits from the glimmer at the top of the pyramid as well. The hype of potentially being the next USL team to get “promoted” to MLS no doubt made the expansion pitch at USL HQ more effective, and has certainly made organizing fan support for new teams easier. That, along with an agreement with MLS that in 2013 brought reserve teams into the league, allowing USL to explode in size to well over 30 teams at its largest.

NASL was not so lucky. A combination of missteps in expansion and ownership choices, and public animosity towards both its competitors, ended with the league effectively closing up shop after the 2017 season, with the remaining viable clubs finding refuge in USL or the fledgling 3rd division National Independent Soccer Association (NISA). USL actually scored a coup near the end of the 2016 season when Tampa Bay and Ottawa announced they’d be switching sides, hastening NASL’s demise. And they’ve have since poached some of NISA’s most successful sides – Miami FC, Detroit City FC and the Oakland Roots.

In 2019, USL launched League One, its professional 3rd Division league, which at the time included several of the MLS reserve teams. But in 2021 MLS shook up the relationship between the two leagues by announcing their own Division 3 league, MLS NEXT Pro (MLSNP), that launched this past Spring, pulling the majority of their reserve teams out of USL’s Championship and League One, and even snagging the independent Rochester Rhinos (rebranded as Rochester NY FC) away from USL. The remaining MLS reserve sides in the USL ecosystem will eventually all migrate to MLS NEXT Pro.

Now the immediate future of the men’s pro soccer landscape is effectively set up as a two horse race (with NISA still trying to find its footing at the D3 level), with the two sides no longer working together.

The Battle Is On

MLS and USL now compete in a soccer space that overlaps more and more each year

MLS and USL now find themselves directly competing for ownership groups, eyeballs, and sponsor dollars at two levels of the men’s soccer pyramid in the USA. And they’re also in indirect competition on the women’s side as well.

Let’s take a look at each area where the two leagues will battle it out:

Men’s Division 3

This is the biggest and most direct conflict between the two is at the Division 3 level. D3 might seem like small potatoes in the grand scheme of things, but the friction between League One and MLS NEXT Pro could have a domino effect that leads to much bigger issues down the line.

Losing the MLS reserve teams themselves to MLS NEXT Pro is actually a net positive for USL. These are teams that nobody goes to see and are otherwise irrelevant outside of MLS hyper-fans interested in seeing developmental players. And USL has enough quality teams at both D2 and D3 to survive the loss of so many sides.

But MLS now fully controls a professional division where they can target ownership groups beyond those ready to immediately join MLS. This is why adding Rochester, and looking to add future “independent clubs” into the league, is such an important detail.

MLS won’t stop expanding as long as they can keep cashing checks for expansion fees. MLS NEXT Pro helps them in two ways on that front. The first is using it as the direct pipeline for future MLS organizations. MLS can simply say to prospective investors “Want to be in MLS? Sure. Start a team in (or move your existing team to) MLSNP first, let’s see how it does, and we’ll go from there.” It could even be a hard perquisite for future D1 expansion (with the MLSNP team eventually becoming the reserve team later on). Make no mistake, MLS NEXT Pro is not only a developmental league for players, it will become a developmental league for markets.

The second is that if and when MLS does finally decide to arrive at a hard cap on the number of teams at the top division, the expansion effort can refocus entirely over to MLSNP. MLS can flesh out its own, insulated minor league pyramid – perhaps someday even including the creation of a second division league.

USL has now almost certainly lost the “MLS expansion hype train” effect that has boosted many of their recent additions. Teams such as Orlando, Sacramento, Nashville and Cincinnati were pretty much launched in USL, and were quite successful, explicitly on the premise of future elevation to MLS.

So now, instead of being the preferred starting spot for the next big MLS expansion team, they must compete with MLS NEXT Pro for markets, venues, and ownership groups. We’ve already seen a contest in Spokane, WA in 2021 between the two leagues, and just this past week Nashville SC announced their reserve team in MLSNP would be placed not locally, but in Huntsville, AL, effectively taking a solid market off the board for USL.

Academies

Both MLS and USL operate youth academy leagues – MLS NEXT and USL Academy / Super Y League. With countless youth umbrella organizations all over the country, this is less of a direct battleground but still an important one, with premier organizations having to pick and choose which outfit to tie themselves to. MLS adding a professional league into their setup, connecting their academy structure directly to the first division, definitely gives MLS an advantage when it comes to youth clubs that aren’t tied to an existing pro team looking at which way to go.

The Women’s Game

The women’s game is where there isn’t a direct confrontation, but the involvement of MLS and USL still could cause some intrigue. MLS has no direct women’s soccer interests, but three of their team ownership groups (Houston, Portland, and Orlando) own National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) teams in their markets. Two USL organizations, Louisville and North Carolina, also own NWSL teams.

In addition to their amateur W-League, in 2021 USL announced the Super League, a Division 2 women’s pro league planning to launch in 2023 with 12 teams (none officially announced as of yet). Intriguingly, D.C. United is apparently planning to launch a team in this league, one that would compete locally with the more established Washington Spirit in the NWSL (a team that currently has a ground sharing deal at DCU’s stadium).

The Super League has also announced that it plans to play on a Fall-Spring calendar, aligning better with the international calendar than the NWSL currently does (at the time of writing, many NWSL teams have been without international players, as the league has played through major tournaments such as the Women’s Euros, W AFCON, Concacaf W Championship and Women’s Copa América).

With a more player-friendly calendar, potentially competitive wages, and some recent stumbles/scandals from NWSL, the Super League could shake up the landscape of women’s pro soccer in the US if the pieces fall a certain way. It’s definitely worth watching where MLS outfits in particular choose to spend their money if/when getting into the women’s game.

MLS vs. USL: Endgame

What does all this mean for the future? It means USL may very well take bold steps to differentiate itself.

USL has made big strides since the NASL exodus on things such as sponsorship and streaming/TV (even recently pulling higher ratings on ESPN2 than MLS national games on the same weekend). But it’s still a league that relies heavily on ticket sales and expansion fees to keep things running smoothly. The hook of possibly someday getting selected to move up to MLS drove a lot of interest from investors and fans in the last decade for USL. But now what?

With MLS building out its own American style “minor league,” and little realistic hopes of any USL side getting elevated to MLS anytime soon, the league definitely needs to amplify what makes it different. If they can’t sell investors on “why should I put (or keep) my team here?” and fans on “why should I watch and/or buy tickets?,” things could start to unravel fairly quickly. But they must tread carefully.

USL has already publicly floated moving to the European calendar and implementing internal promotion and relegation on the men’s side as ways to move forward. These types of changes, if done smartly, could not only solidify USL but seriously elevate it.

But these are also the kind of things that, if done recklessly, could send the league towards a downward spiral into disaster. One misstep, or an injection of unneeded ego and bravado into the equation could spell doom for not just the league but many clubs as well. Yes, USL has done more of the ground work in building a robust infrastructure and substantial base than NASL ever did. They’ve certainly walked more of the walk. But as someone who lived through the NASL collapsing in on itself and lost both the club they loved *and* their job on the same day, it’s setting up to be a scary time for the game and everyone in it. If USL goes too far, takes one risk too many in an attempt to stand out, it could lose much of the ground it has gained.

Ideally, there is space for everyone. MLS gets its developmental pyramid and USL continues to grow and thrive in its own space as a place for “independent/authentic” soccer, and everybody wins. The darker path, where USL tries (and fails) to upend the status quo in a frantic effort to compete, could leave us with only a smattering of minor league outfits and a soccer nation much worse off than it is now.

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season