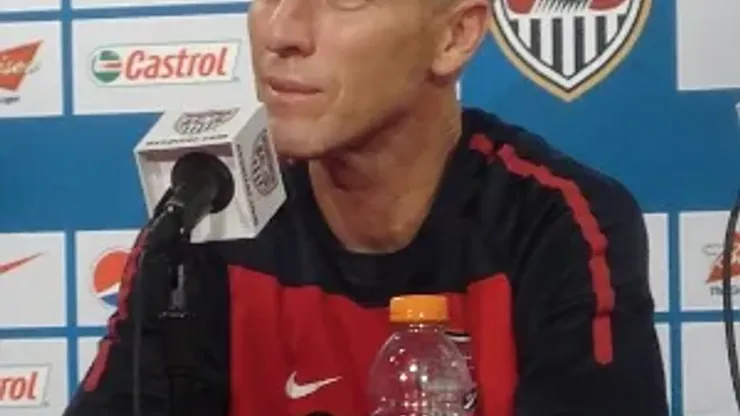

One of the positives Bob Bradley has brought to the United States Men’s National Team is formation stability.

Whereas Bruce Arena employed an admirable adaptability, Bradley’s move to an unvarying 4-4-2 has given his players consistent time within one system, allowing them to master its intricacies, the virtues of which can be seen in the States’ skill on the counter.

In the wake of his late-summer interview with Sports Illustrated’s Grant Wahl, Bradley’s approach is often described in terms of Italy, given his stated admiration for last decade’s AC Milan teams. But the current set-up became popular thanks to its success with Brazil, where it has become common to adapt central defenders who have distribution talent to pivot roles in a 4-2-2-2.

While this formation leads to a huge gap in the middle of the pitch (making link-up play difficult), Brazil augments this approach’s deficiencies with the athleticism and dynamism of their four main attackers. Think Kaká, Fabiano, Robinho.

The U.S.’s success with this set-up has come as Landon Donovan, Clint Dempsey, and Charlie Davies settled into their roles. Once Bob Bradley acquiesced to using Donovan and Dempsey as wingers, it gave Davies a route into the team, giving the United States enough firepower to offset what is an inherently conservative approach.

But whereas Brazil’s depth of talent will allow them to stay in this system through injuries and dips in performance, the United States’s talent pool is not as deep. If injuries occur, the United States will have difficult finding players to fill the four key attacking roles.

Depth becomes a bigger issue when some of the program’s key talents have no spot in this specialized set-up. Some of the players who do have spots have been forced to adapt their styles to the system.

In addition, at central midfield, where the U.S. has a reasonable depth of talent, limiting the team to two players of a certain type means many talents face increased competition.

Expanding on Issues: A Shorthanded Attack

While the United States has three very good attackers (Donovan, Dempsey, Davies) and a prospect (Altidore) whose potential for growth justifies his continued inclusion, there have been recently been questions surround three of those four options. Davies and Dempsey are recovering from long-term injuries and are still doubts for South Africa. Thankfully, Jozy Altidore has found a strong run of form at Hull City after a fall that looked to compromise his development.

Through all this, the other attacker – Landon Donovan – has continued to be the most reliable player in the national team set-up.

If the States had to replace three of their attacking four, would it make sense to stay with a system so reliant on these four attackers?

We have seen Stuart Holden’ mixed results (Gold Cup, compared to Honduras), a perfectly acceptable rate of development for a player so young. Robbie Rogers has been similarly inconsistent, while the replacement forward options are also problematic. Conor Casey had a good performance in Honduras, but those are his only international goals, while Brian Ching’s virtues are lost without a player like Davies playing off him.

If the United States ever had to go with Casey, Donovan, Holden and Rogers for a stretch of matches, would they be best served keeping the current formation?

Possibly, possibly not, but the current inflexibility leaves no choice. The lack of options only exacerbates the drawbacks of the 4-2-2-2.

Expanding on Issues: Central Midfield Depth, Two Spots

In the Brazilian system, the key to the two central midfielders’ value is ball-winning ability and distributing diagonally to the wings and forwards going wide to win balls.

Perhaps this explains the United States’ reliance on the counter attack. The U.S. has no players playing the deep midfield roles who can consistently provde this type of distribution (let alone overcome the formation’s problems and link-up conventionally). Michael Bradley could be this type of player in a more traditional, central midfield role but not from a defensive position to which he is less-suited.

In the current set-up, the U.S.’s best option for the pivot positions is to rely on their best ball winners, but Jermaine Jones and Maurice Edu have had fitness issues that could keep them from settling-in before South Africa. Ricardo Clark is the next-best option, showing consistent improvement over the last year, becoming the States’ best ball-winning midfielder.

Michael Bradley has valiantly played this role, slowly adapting over the qualifying cycle, but his talents are wasted in this spot. In addition, his tackling is not his best skill, often putting him in a bad position as a central midfielder. He may never be able to avoid the constant threat of yellow and red cards should he continue to be deployed in this role.

Bradley would be better in a pure, central midfielder’s role, if not a more attacking position (like he played at Heerenveen). His father’s system has forced him to be shoehorned into a role to which he is not suited.

Michael Bradley is not the only player without a natural spot in the 4-2-2-2. Kyle Beckerman, Jose Francisco Torres and Freddy Adu are also players who may need to change their games. And where do younger players like Chris Pontius – or even Stuart Holden – fit?

Perhaps they don’t, but in lieu of a deep talent pool like Brazil’s – where a player like Anderson could come in and replace Felipe Melo, even if a player like Diego doesn’t have a role – the United States faces a troubling choice when people get hurt:

Stay with a 4-2-2-2 that would exclude that match’s best options, or develop a back-up plan?

Alternative: Of Pyramids and Christmas Trees

The United States’ success with a 4-2-2-2 makes it difficult to abandon it, but Bradley should have at least one other option to fall back upon in case of injury or bad match-ups. Given the United States’ depth in central midfield, its swallow pool at forward, that fall-back should be a 4-3-2-1.

Ironic because of Bradley’s Italy deference, his choice club – AC Milan – exclusively employed a 4-3-2-1 at the end of Carlo Ancellotti’s tenure.

Like the U.S. Men’s National team, Milan had a lot of depth at the 3-level (Andrea Prilo, Gennaro Gattuso, captain Massimo Ambrosini, Mathieu Flamini and players who could occasionally play at that level: Clarence Seedorf, David Beckham).

Like the USMNT, there was a thinning crop of forwards, where an aging Filippo Inzaghi continued to top the pyramid (or, Christmas tree) before this year’s switch to a 4-4-2 (and then a 4-3-3).

As would be the case with Bob Bradley’s team, AC Milan has had creative presences at the 2-level that were able to express themselves with the relatively free roles afforded by this system. Most famously, Kaká exploited this, but Seedorf, Alexandre Pato and Ronaldinho also saw benefits from this set-up.

For the United States, Landon Donovan and Clint Dempsey would be perfect fits at the 2-level, where Charlie Davies could also play there. This could also be a better fit for players like Torres, Adu, and Holden.

Playing with three central midfielders in a 4-3-2-1 could also offer protection for a back line that can have its relative lack of quickness exploited.

This summer, we have seen strong performances (Spain) from a United States central defense that featured Oguchi Onyewu and Jay DeMerit, but if you get either of those two moving laterally, they can be consistently beaten. Having three central defenders who can play deep helps keep the opposition from easily moving through the back line’s gaps.

With three central midfielders, you can are also less-reliant on players like Bradley, Feilhaber, and Beckerman being ball-winners. Again, we turn to AC Milan for an illustration. Andrea Pirlo has played a deeper role for the recent Milan sides, but he’s never had to be a hard man. That’s been Gattuso. That’s been Ambrosini (to a certain extent).

Michael Bradley, in a 4-3-2-1, could play slightly above players like Jones and Edu and Clark. With a more ambitious deployment, the USMNT could better utilize Bradley’s skill, helping the team to better link-up play through the middle of the pitch.

Having three players in the deeper positions of midfield would allow one (or more) of the Jones, Edu, Clark trio to jump into attack, leaving up to two players back to protect. The midfield trio could pick-and-choos their opportunities to get forward without leaving the team exposed.

The Need for Flexibility

The 4-3-2-1 could turn into a better option for the 4-2-2-2. It’s a better fit for the program’s personnel, and it allows for more on-field, tactical flexibility than the current set-up.

But the current approach has been proven to work. The players have developed a certain expertise, allowing them to give performances like the one we saw in Honduras. Even so, the ability to switch to a 4-3-2-1 could be a valuable in-game tactical option, whether it be to preserve a lead or to augment play when the United States struggles though the midfield.

Even if the 4-2-2-2 remains the preferred option, the fitness and form issues that have plagued the United States’ attackers make a 4-3-2-1-option a beneficial fall-back.

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season