There are some players that don’t look quite right in their shirt numbers.

Etched into our soccer consciousnesses are intangible, requisite criteria when it comes to the number a player should have emblazoned on the back of his jersey. It’s the reflex that niggles at us when we see Samuel Eto’o donning No. 5 for Everton, or the uncomfortable feeling that festered when William Gallas wore No. 10 for Arsenal.

As supporters, we know these numbers are a bit peculiar, but why does something so trivial irritate us? Where does this seemingly inherent instinct emerge from? And why is it such a big deal anyway?

Naturally, to fully understand it, we need to take a few steps back.

The man that much of this is ultimately down to is legendary Arsenal manager Herbert Chapman, who pioneered the idea of numbered strips in a match with Sheffield Wednesday back in 1928. In the aftermath, the idea was cast aside by English football’s governing body, but after various reported instances of sides wearing them for the next decade or so, it was decided that all players should wear numbered shirts in 1939.

A brief foray into Chapman’s methodologies will reveal he was something of a visionary, and the underpinning motivation behind numbered shirts was that it’d allow his players to maintain an awareness of where they are in relation to their teammates on the pitch. And it set in motion the process for the classic 1-11 that is still adhered to today by many international teams today.

Chapman numbered his players in ascending order, beginning with the goalkeeper and then moving forward from right to left and up the pitch. So in the 2-3-5 system—the most popular during that particular era—the two defensive players wore 2 and 3, the three midfielders donned 4, 5 and 6, while the five across the front wore numbers 7 to 11.

But as that system became outdated and superseded by the W-M and eventually 4-4-2 et al, the numbers shifted around the team. 2 and 3 eventually pushed wide to play right and left back respectively, while two players from the central midfield area—numbers 5 and 6—dropped back between them to form a back four. 7 and 11 maintained their width, but dropped back to flank 4 and 8—who also moved deeper to make a four-man midfield. 9 and 10 remained up top.

Here’s a look at how the changes happened:

When substitutes were eventually introduced in 1965, they were allocated ascending numbers from 12 upwards, although if those on the bench were of a superstitious disposition, they could decline wearing the No. 13 shirt.

In England, players were assigned those numbers on a match-by-match basis. So during that era, even the greatest players didn’t really have a number that was wholly synonymous with them. When George Best, a player typically associated with the No. 7, was at his majestic best for Manchester United, he’d don myriad numbers depending on where he’d start on the pitch.

While that was the case in England up until the inception of the Premier League, across the globe and on the international football scene, things were a little different. The most notable example perhaps being Argentina.

When the Albiceleste named their squads for the 1974 and 1978 World Cup. Instead of going with their own traditional methods—which would see the right-back wear No. 4 amidst other minor variants from the archetypal English model—they decided to allocate their numbers to the squad in alphabetical order of the players’ surname.

So Ossie Ardiles, an intricate, technical midfield player, would regulary be seen in the No. 1 jersey.

As shirt numbers became an increasingly big deal though, exceptions were made. The Argentinean squad for the 1982 World Cup were once again allocated their numbers alphabetically, but one player was allowed to choose his: Diego Maradona.

The man subsequently dubbed “El Diez” and his No. 10 Albiceleste shirt are perpetually iconic, so much so that the Argentinean Football Federation tried to retire it in 2001.

But it was quickly thrust back into the fold when FIFA demanded the nation enlist 23 players for the 2002 competition all numbered from 1-23 accordingly; Argentina submitted a list containing 1-9 and 11-24 instead. So Ariel Ortega was eventually given the honor of wearing the shirt for that tournament, and now Lionel Messi is a seemingly worthy bearer of it.

At club level though, there’s a lot more freedom when it comes to shirt numbers. When the Premier League and the rest of Europe’s more illustrious divisions abolished the notion that the starting XI had to don 1-11 back in the early 90s, clubs and players could essentially do what they want.

Indeed, Maradona may not have his No.10 out of commission at national level, but at Napoli—where he is a deistic figure after inspiring the Partenopei to the Scudetto—it’s retired in tribute to the diminutive genius.

At Milan, Franco Baresi and Paolo Madini’s respective No. 6 and No. 3 shirts are both retired, but in the case of the latter, if one of Maldini’s sons—both Daniel and Christian Maldini are currently in the Rossoneri academy—were to progress into the first team, then they’d be afforded the honor of wearing their father’s shirt.

Shirt retirements are scattered across the footballing world. Clubs ranging from Bayern Munich to Portsmoth even retire the No. 12 in recognition of their supporters as the “12th man”. But with shirt numbers going out of action seemingly year-by-year, players are having getting a little more creative with their choices.

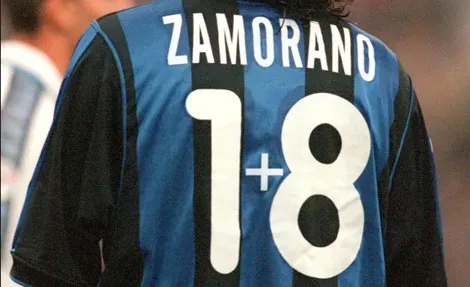

When told he would have to vacate his No. 9 shirt at Internazionale for the incoming signing of Brazilian superstar Ronaldo, Ivan Zamorano opted for the No. 18, but decided to print a little plus sign in between them so he was still No. 9. Sort of, anyway.

There’s also been some unpopular choices. Juventus supporters protested vehemently when Carlos Tevez inherited Alessandro Del Piero’s No. 10 jersey, although the striker’s stellar performances in the Bianconeri strip put pay to those worries.

Even more controversially, Gianluigi Buffon received enormous criticism when he asked to wear the No. 88 during his time at Parma. The letter H is the eighth letter in the alphabet, and subsequently there were members of Italy’s Jewish community who felt the number represented “HH”, often shorthand for “Heil Hitler”!

Buffon offered an alternative explanation, though, per The Guardian:

“I have chosen 88 because it reminds me of four balls and in Italy we all know what it means to have balls: strength and determination.

“And this season I will have to have balls to get back my place in the Italy team.”

Now it’s commonplace to see unorthodox numbers in every squad in the Premier League. Indeed, Mario Balotelli and Lazar Markovic have chosen to wear No. 45 and No. 50 respectively at Liverpool, despite the traditional No.7 and No. 11 jerseys being available.

And as commercialization has crept into the game, the decisions these players make are becoming an increasingly big deal for the marketability of them and their clubs; to be a bespoke commodity in a game saturated with personalities is becoming increasingly difficult, after all.

So players hold few concerns for the traditional associations with various numbers. Now players will pick lucky numbers, year of birth or numbers that their boyhood idols wore and even numbers to symbolize their rapper alter-egos! And that’s to name but a few.

But there are still some nods to tradition and heritage. When England play their friendly games they’ll wear the classic number arrangement based on their positions on the pitch, as will a host of various national teams, something that’ll still make purists purr with nostalgia.

As for our aformentioned duo, Eto’o apparently decided to wear the No. 5 for Everton because it was the shirt he was allocated by Cameroon on his first ever appearance for the country. And Gallas was given the No. 10 at Arsenal because Arsene Wenger insisted that no striker could come close to replicating the impact made by its former occupany Dennis Bergkamp during his glittering spell in Arsenal red, so he gave it to a defender instead.

Shirt numbers are not the most important facet of the game by any means, but they’ve brought wondeful symbolism and esteemed relevance to a host of players throughout the history of soccer. And as the struggle to be unique becomes increasingly critical for the big players that dominate the footballing landscape, it’ll be interesting to see what’s next in store for us when it comes to what’s printed on the back of a shirt.

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season