The speculation surrounding the early history of soccer in Latin America is akin to a Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel.

Fantastical rumors surround the founding of club teams and murder abounds as conjectures and lies paint an uncertain picture of what soccer was really like a century ago. With few if any primary sources left to tell the tale, we must comb through the records to find reputable players and spectators that can provide insight into the state of soccer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The following quotes act as snapshots of the ethos of a century ago and articulate the development of soccer in Latin America.

“During the voyage out from England, I had heard that cricket was played in the country, but supposed it would turn out to be cricket of that degenerate sort which one finds occasionally played by the English residents in different parts of Europe. So that when I got to the ground, and found an excellent pavilion, a scoring-box, visitors’ tent, the field marked out with flags, with the well-known letters M.C.C. (Mexico, not Marylebone, Cricket Club) marked upon them, and some eighteen or twenty players in flannels and cricket shoes, I was not a little astonished, and soon found out that I had to do with a very different sort of cricket to what I had expected.” – W.H. Bullock

As backwards as it may seem, cricket, not soccer, was at one time the most organized sport in Latin America. Heavy English investment throughout the Americas saw immigrant workers from the UK export the game of cricket. Having already been firmly established in the UK since the 18th century, it was only natural that English immigrants now working in the Americas would bring with them their favorite sporting pastime. Where there were English, there was cricket. One of the earliest cricket clubs, Mexico Cricket Club, was founded in Mexico City in 1827 by English mine owners and businessmen. 1842 was the inaugural year of Uruguay’s first cricket club, Victoria Cricket Club, founded in Montevideo.

By the mid-19th century, multiple cricket clubs could be found in nearly every country in the Americas. Even the USA caught cricket fever as evidenced by the cricketer and entrepreneur Fred Lillywire, “Cricket in Philadelphia has every prospect of becoming a national game,” before having its fervor quickly cooled by the boom of baseball. Despite cricket clubs popping up around the continent, only the British and those from the upper echelons of society really adopted soccer. Most locals equated the game with British imperialism. It wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century when soccer began to sink its roots into the fertile soil of Latin America.

“Made up in the main by smaller and quicker players… physically inferior compared to its rivals, Nacional abandoned physical encounters that were allowed back then… They chose dribbling, fast and short passes, quick sprints.” – Del fútbol héroico

As is to be expected, football in the Americas was largely influenced by the English. Having seeded the game in the Americas, the early style of soccer was identical to that of England, which is to say brutal, simple, and direct.

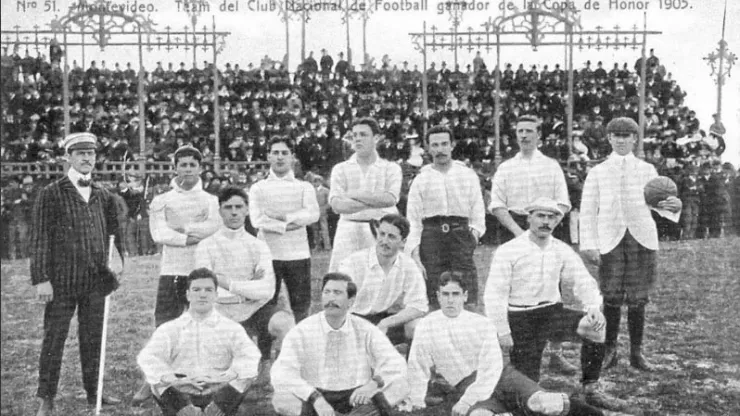

Nowadays we have come to associate Hispanic fútbol with that of flamboyance, individualism, and beauty, but it didn’t start off that way. While nearly all football clubs in the Americas were founded by Englishmen, Nacional of Uruguay was founded and fielded only by Uruguayans. Its willingness to break away from English influence led it to search for its own style of play. Instead of playing like a gang of brutes, the patriotic club decided to adapt its game to its personnel and emphasize dribbling and passing rather than route one play.

The charging of attendance fees also served as the impetus that turned soccer players into performers. A tactical philosophy that centered around quick passing and deceptive dribbling led Nacional to not only domestic but international greatness when the whole of the Nacional players were called to play for the Uruguayan national team in a match that ended with Uruguay winning their first international match against Argentina in 1903. Soon, through Scottish and nationalistic influence, fútbol played in the River Plate and throughout the Americas would come to find its own style of soccer.

“El Negro con el Alma Blanca” – Nickname of Afro-Uruguayan National Player Isabelino Gradin

The black with the white soul was what Uruguayan fans called their beloved national team player Isabelino Gradin who along with his teammate Juan Delgado –nicknamed The Black Juan- were the first two black players to play international football in 1916. Perhaps the two players would have gone down as self-effacing footnotes in the history of Latin American fútbol had it not been for an official complaint lodged by the Chilean Football Association accusing the Uruguayan side of having fielded two “African slaves” in their 4-0 loss of the first ever Copa America tournament. In the face of overt racism, Uruguay went on to win the tournament as well as the subsequent one. As can be inferred, even though Uruguay fielded black players, fans couldn’t help but comment on their blackness. While Uruguay may have been accepting of blacks in professional sports in the early 20th century, their neighbors to the north would only start welcoming players in the 50s. Brazilian writer Mario Filho summed it up when he lauded Pele and the 1958 World Cup winning Brazilian team with having “…completed the work [the abolition of slavery] of Princess Isabel.”

It wasn’t even until the mid-1960s when storied Brazilian club Fluminense started employing players of non-European ancestry. While Uruguay may have been relatively accepting of blacks, other South American nations took a little longer to integrate those of color into their sides.

“During the week, he traipsed around the streets of the capital, making a meager living as a street vendor, but came into his own on the pitch on Sundays. By Mondays, however he was so exhausted that he could not work. He proposed that the club pay him the two pesos that he might have earned on the Monday so that he could play on Sunday. Otherwise he threatened to quit.” – Golazo!

During the turn of the century, soccer players weren’t bringing home big money or gaining national recognition. During the early 20th century, professionalism was still a few decades away. Soccer players didn’t earn the majority of their money through sports. It wasn’t until after spectators were being charged by clubs that players began demanding money for their service. The player that the quote is referring to is a man named Zanessi that ran the pitch for Dublin Montevideo. As is to be expected, the quality of play and player wages simultaneously increased. Despite being trounced by visiting European clubs in the early 20th century, the gradual adoption of professionalism Latin American soccer began catching up to the play of their founding fathers across the pond.

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season