As most of you know, working at the same job year after year after year can cause burnout. Doing the same thing relentlessly reduces efficiency, and it’s known that varying activities or swapping responsibilities on a rotating basis can keep the mind fresh and body willing. It is not necessarily that you are technically incapable of doing your job; more that it becomes harder with experience and time.

There is no reason that would be different for a footballer. After all, the most exciting thing in football, as in much of life, is the thrill of the new. A new player at your club, or a new manager, can spur on a team to success. Novelty refreshes even the oldest player or fan. Even Alex Ferguson, a man who rarely overhauled his side, made sure that a couple of new faces cropped up in most transfer windows. Only those rare players, hungry to win throughout their career, were retained for most of his career.

However, for athletes, it’s not just the mental strain that builds up. It’s the physical damage, too. The body is generally strengthened by regular activity, but constantly putting yourself through unusually tough rigors will have long-term effects. Gabriel Batistuta, for example, wanted to have his legs amputated, such was the pain he endured after he retired. Even more seriously, there are theories that heading old balls may have given players degenerative brain conditions; similarly, there are links between concussion and NFL and rugby that become ever stronger. It is rare, even, that you don’t see a committed amateur roadrunner who doesn’t nurse some kind of joint problem.

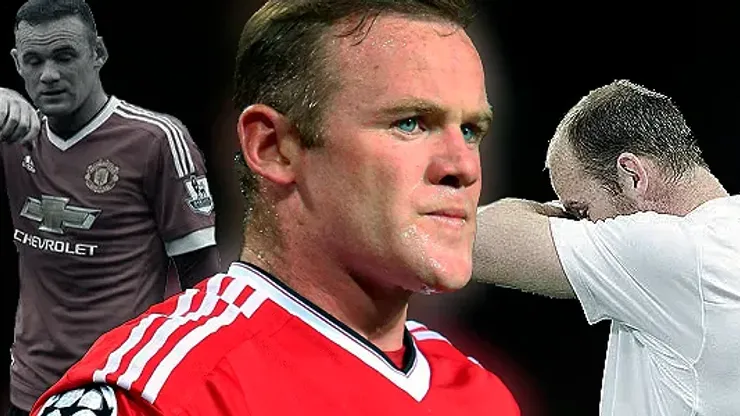

In soccer, the best example of this might well be Wayne Rooney. He made his debut at 16 for Everton, 17 for England, and 18 for Manchester United. The success of United and the presence of England at most major tournaments mean that Rooney has played 568 domestic games and 107 for England. He is only now on the cusp of turning 30. It’s true that Rooney has avoided the most serious injuries, but he has been regularly hampered by metatarsal injuries and various muscle strains, and weighed down by his own occasional Christmas excesses. He features for club and country not because his form warrants it, but because his managers keep waiting for his former self to return.

There is, of course, no perfect solution, because the human body is not perfect. As remarkable as it is, it has an inbuilt expiration date, and some people’s genes are more conducive to being hard-wearing than others. John Terry, for all his faults, seems like the kind of man who could be shot at a wall with a cannon and only need a couple of hours to recover. On the other hand, there are athletes who go through the horror of their early 20s when their knee repeatedly buckles under strain and eventually find themselves out of work, with nowhere else to go.

SEE MORE: Rooney denies documentary claim he asked for a transfer before Ferguson’s retirement.

What is just as interesting, though, is how the average top-level professional soccer player (or other athletes) can extend their career. For sports like NFL, ice hockey, soccer, rugby, basketball and cricket, 30 generally is seen as the turning point of an athlete’s body. However, it is now accepted that with best practice and no little luck, that can be extended for the best part of a decade. Think of AC Milan’s defense, Ryan Giggs, Mark Ramprakash, Michael Jordan and Steve Nash – all more capable of staying close to the top of the game than almost any other player, whatever the age.

There’s a theory now, though, that if you break into professional soccer before you’re 20, like Rooney, your time may come to an end sooner. That’s because there’s a magic figure of 700 games, sometimes lower than that. At 700 games, injuries catch up and become cumulative. For other players, that figure might not come until 33 or 34, or even later, and that perhaps explains the longevity of some. Giggs, for example, might have had a hamstring problem, but over the course of his two decades of professional football, it was rare that he played fewer than 30 games or more than 45. Now it is not unusual to see players like Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi or Frank Lampard play more than 50 or 60 times in a season. Andi Thomas wrote about this for SB Nation recently, and it is worth your time.

SEE MORE: A conversation with the man who discovered Wayne Rooney.

But there appears to be a method, though it is severe, of extending a career. Not only does it appear to reinvigorate the body, but it gives players a rediscovered appreciation of their sport. Essentially, it is a fallow year, or a sustained break from the sport’s greatest demands. Paul Scholes, Lassana Diarra and Steed Malbranque recently took long periods of time off only to come back refreshed.

The circumstances were varied. Scholes had a serious case of double vision, and skipped half a season. He later retired, missed another season, and came back to steer United to another title. Only in the very last stages of his career did he start to become a liability due to the slow movement of his body. Before then, his form had occasionally dipped, but each return marked an uptick in performances. It appears that the breaks did his career no harm at all, and without it being possible to prove, the time off may well have improved it.

SEE MORE: Van Gaal targets derby win to prove United’s title credentials

Steed Malbranque’s circumstances are odder, admittedly. Malbranque spent 2006-2011 at Tottenham Hotspur and Sunderland in an unremarkable five years. He didn’t embarrass himself, and a first-team regular, but there was nothing special about him. In 2011, he left the Premier League to join Saint-Etienne, and in a big ball of confusion, left after a single game. For the 2011-12 season, that was all he managed. He considered retirement, but the following season he joined his first club, Lyon, putting in performances of such quality that there were calls for him to be given caps for the international side.

The most recent example is Lassana Diarra, whose peripatetic career spanned most of Europe’s breadth, but until he joined Marseille in the summer, seemed to be heading for an end caused by contractual limbo. He kept training with former clubs, but he didn’t feature in competitive soccer for more than a year. Yet here he is, back playing at the peak of his powers, a rare bright spark for Marseille, and with a chance to feature for France in Euro 2016. Another year off, another success.

There are similar stories in other sports. Australian cricketer Shane Wayne was given a ban for using diuretics but came back with such vigor that writer Gideon Haigh appraised the ban as a ‘performance enhancing risk.’ Michael Jordan’s baseball folly didn’t prevent him from being the greatest basketball player of all time. But of course the greatest example remains Eric Cantona,. Banned from soccer for eight months for kicking a racist cockney in the head, Cantona came back with an unblemished reputation to give United the title. And, when he knew he wasn’t at the top of the game, he chose the other option – to leave the sport behind and achieve excellence elsewhere (his chosen field of excellence: being the best human in the world).

What this has to do with Rooney, then, is the recommendation that he takes a year off. He is no use to Manchester United team in this state, and he is no use to England country either. He is possibly the worst player in the Premier League at the moment, such is his poor form. It is not just physical, despite his alarming shortcomings, but his mind, too. You don’t lose your first touch because you’re getting on in years. You lose it because your concentration has disappeared.

Of course, it would be difficult, and it would be commercially costly to him and his sponsors, but there comes a time he must ask himself: in his current state for Manchester United and England, is he really there anymore anyway?

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season