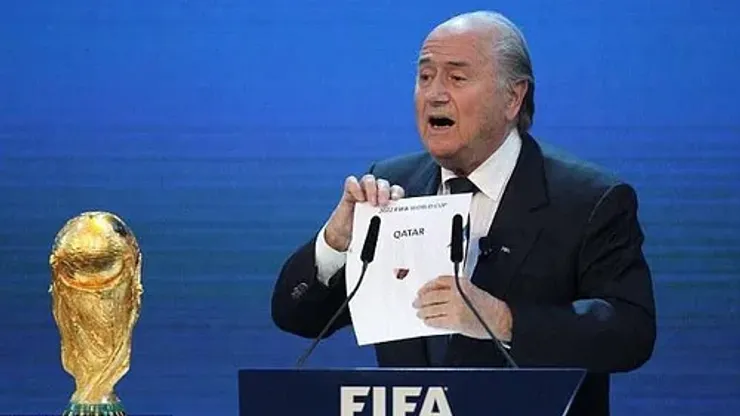

It is firmly advisable that one needn’t even attempt to come up to speed with developments in this summer’s – probably the next eight summers’ – most absurdly gripping parlance without first flushing a number of distractingly obvious thoughts out of the mind. In getting to grips with the decision – looking more likely with each bumbled and blundering press release – that the 2022 World Cup in Qatar will be moved to the winter months to avoid the wasting heat of the summer in the appointed emirate, a couple of unanswerable questions need to be served up, sniffed at and then chucked into the bin before morbid curiosity leads us to make the fatal mistake of shoveling in a noxious mouthful of Haute Blatter.

For the entree, why, after a probing bidding process during which every assurance was given that a summer tournament was possible in the region and no one at FIFA felt moved to conduct any kind of study into the feasibility of staging 90 minutes of football in 50 degrees plus conditions, are we only now fretting that Qatari officials may have promised, if not the impossible, then at least the humanly implausible? That’s your garlic bread – a predictable starter that offers no surprises but without which what follows would somehow feel unfathomable. Follow that up with a main course of logistical mind benders about how on earth the European calendar will ever be able to re-shuffle itself to allow for 2 months off in the winter and then back again, doing one’s best to eat around Blatter’s casual musings that the whole arrangement “will only affect one season” (the league employees who begin drawing up fixture schedules three years in advance will find that thought particularly indigestible). Afterwards settle the stomach with a snifter of accusatory questions on why, now that Qatar has been shown by all available medical evidence to be unable to meet the terms of the agreement that gave them their prize, are alternative locations not being seriously considered?

These thoughts were all brought to the table back in 2010 and will continue to be chewed upon until long after the tournament is done and dusted. But it would be impossible to really get to grips with the more subtle points of the issue without first picking these particularly distracting pieces of gristle out of the teeth. They all now promise to be part of the landscape for the next decade and football has well and truly tied itself in another knot in its unending quest for growth. It might even be put that the likes of the Premier League and its stars have no right to complain about FIFA putting its own corporate interests first at the expense of its contemporaries when such hegemonic domineering has been the League’s blueprint for more than twenty years. To the game’s power-brokers we might say “it’s your dime”. But what about the others from outside the barbed perimeters of corporate soccer, for whom a domestic football season pushed into the summer months would leave precious little room in which to operate?

Domestic football protects itself internally against TV coverage of big games draining attendances at lower league matches by setting restrictions on what can be broadcast and when, but no umbrella body exists that can both exercise control over the Premier League and also has vested responsibility in the health of cricket, rugby league, tennis and other sports that traditionally thrive during the football hiatus. Far from operating under the banner of a co-operative, football and the summer sports will find themselves in 2022 in a dispute over territory.

As Blatter is so keen to remind us, the change will occur for only one season. Considering that complicated yearly schedules that flow in and out of one another are unlikely to prove flexible enough to flip their focus twice in a 12 month window that claim feels over-confident, but even allowing for the minimum possible disruption the outlook is bleak for some.

Between 2011 and 2012, 16 out of 18 first-class county cricket clubs suffered falling average attendances year on year — in the case of Lancashire by as much as 45%. Quite what impact the added competition for spectators from Manchester United and City will have in the region on a sport already battling to remain current in the sandstorm of a digital revolution is difficult to judge from this distance, but the challenge is unlikely to come only from the mega rich. Blackburn, Bolton and Burnley are all likely to be playing in the top two divisions in 2022 and the likes of Bury and Rochdale, already swept up in their own struggles to keep fans passing through the turnstiles, will fight fiercely to cling to their market share on a Saturday afternoon. Even a single summer of intensified competition for fans could prove unbearable for those outfits from both sports whom don’t have the safety net of multi-million pound broadcast contracts to keep them solvent.

Don’t expect the FIFA Exec Com to lose too much sleep over the relative health of English domestic cricket, or any other industry around Europe that has its long term plans linked wilfully or by circumstance, tightly or contingently to the timings and movements of the football behemoth.

But expect plenty of sob stories coming from the Premier League over the coming years about the indignity of being shunted around by a fat-cat outfit twisting and re-shaping the game for its narrowly defined corporate ends. Who knows, maybe an enforced dip in the chill waters of irony will do the domestic game some good – certainly it would make a nice change for a World Cup to leave a positive legacy behind rather than the usual white elephant infrastructures that no longer have anything to inhabit them. But spare a thought for the real victims of this undisguised crusade of profiteering and thoughtlessness. Because the sanctuary of the summer months may soon see its boarders breached leaving little to no protection for those dwelling there.

200+ Channels With Sports & News

- Starting price: $33/mo. for fubo Latino Package

- Watch Premier League, Women’s World Cup, Euro 2024 & Gold Cup

The New Home of MLS

- Price: $14.99/mo. for MLS Season Pass

- Watch every MLS game including playoffs & Leagues Cup

Many Sports & ESPN Originals

- Price: $10.99/mo. (or get ESPN+, Hulu & Disney+ for $14.99/mo.)

- Features Bundesliga, LaLiga, Championship, & FA Cup

2,000+ soccer games per year

- Price: $5.99/mo

- Features Champions League, Serie A, Europa League & Brasileirāo

175 Premier League Games & PL TV

- Starting price: $5.99/mo. for Peacock Premium

- Watch 175 exclusive EPL games per season